Monki Gras 2024: Step… Step… Step…

Yesterday I gave a talk at Monki Gras 2024. This year, the theme is “Prompting Craft: examining and discussing the art of the prompt in code and cultural creation”. I did a talk about my experience of learning these new AI tools, and I draw comparisons to learning to dance.

This is my third time at Monki Gras, and my second time speaking – I first went in 2018, and I gave a talk about the curb cut effect in 2019. I bought a ticket as soon as they went on sale – I enjoyed myself so much at previous events, going again was a no-brainer. (My ticket was reimbursed because I was speaking, but I’d have happily paid to go anyway.)

Monki Gras is a rare event that manages to have both good talks and a good hallway track. The first day of talks had a lot of interesting ideas and were well-presented, and I had some thoughtful and friendly conversations in between. I know I’ll be thinking about the event for weeks to come, and there’s still another day to go!

I’m pleased with the talk I wrote, and people seemed to enjoy it. The talk wasn’t recorded, but I’ve put my slides and notes below. (I wanted to get these up quickly, so there may be silly typos or mistakes. Please let me know if you see any!)

This is the key message: being a good user of AI is about both technical skills and managing your trust in the tool. You need to know the mechanics of prompt engineering, what text you type in the box, yes. But you also need to know how much you trust the tool, and whether you can rely on its results – if you don’t, the output is useless.

What a lovely sense of ~gender~

There are some personal reasons why Monki Gras feels a bit special.

I went to the last Monki Gras in 2019. It was cancelled in 2020 thanks to COVID, and this is the first year it’s been back – five years later! A lot of stuff has changed in that time.

In 2019, I was starting to explore what being genderfluid might mean for me, how that might affect my professional career, and I had several meaningful conversations with now-friends at Monki Gras. In 2024, I have a better understanding of what my gender looks like, I’m much happier, and I’m more comfortable presenting as my full self.

At both events, my gender and my appearance have been a complete non-issue. People accept that I am who I say I am; there were no awkward stares or questions; I was never misgendered. I got to relax, and focus on the event rather than worrying if somebody was about to be weird.

It’s nice.

This should be the norm at professional events, but it isn’t, and it’s a bit sad that I can’t take it for granted. But it’s nice when it happens.

Links/recommended reading

-

There are lots of books about the history of swing dancing and jazz music. I read Swing Dance by Scott Cupit as I was writing the talk because it’s what I had to hand, but there are plenty of others. It’s a fun subject!

If you’re getting started, I’d particularly recommend looking for information about Frankie Manning and Norma Miller, two of the early pioneers of this style of dancing.

-

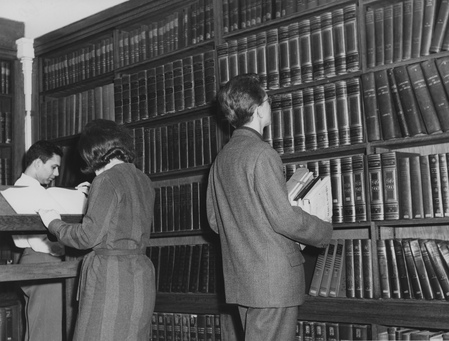

Most of the photos in the talk come from the Flickr Commons, a collection of historical photographs from over 100 international cultural heritage organisations.

You can learn more about the Commons, browse the photos, and see who’s involved using the Commons Explorer https://commons.flickr.org/. (Which I helped to build!)

Slides and notes

Introductory slide.

It’s lovely to be back at Monki Gras.

My name is Alex Chan; my pronouns are they/she; I’m a software developer.

I work at the Flickr Foundation, where we’re trying to keep Flickr’s pictures visible for 100 years – including many of the photos in the talk. I do a bunch of fun stuff around digital preservation, cultural heritage, museums and libraries, all that jazz. If you want to learn more about my work and all the other stuff I do, you can read more at alexwlchan.net.

But I’m not talking about my work today. Instead, I want to talk about dancing. A few years ago I started learning to dance; last year I started learning to use AI, and I’ve spotted a lot of parallels between the two. I want to tell you what learning to dance taught me about learning to use AI.

This all started about five years ago. I was in a theatre at Bristol, watching a musical, and as musicals are wont to do, they had some big song and dance numbers.

I was sitting in the audience, and as I watched the actors dancing, I thought “that looks fun, I want do to that”. So in the interval I got out my phone, I started reading about dancing, and what they were doing on stage.

The particular style of dancing they were doing was called swing dancing.

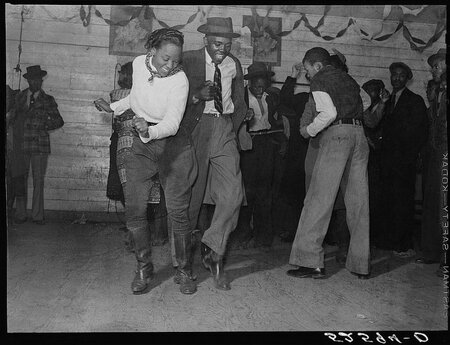

Swing dancing is an umbrella term for a wide variety of energetic and rhythmic dance styles, usually danced to jazz music. Probably the most well-known is lindy hop, but it also includes balboa, jitterbug, charleston, collegiate shag…

Swing dance came out of the African American jazz scene in the early 20th century, and a lot of the moves practiced today have their roots in traditional African folk dances.

Swing dancing is very popular today, and there’s a thriving swing dance scene in London, so I was able to find a beginner class just five minutes from where I was working at the time. It was closer than the nearest Starbucks!

This was a proper beginner class, no experience needed – which was good, because I didn’t have any! You could walk in having never danced before and they’d teach you from scratch.

This is great for students, but it poses a tricky challenge for the teachers. Many people are quite nervous in a dance class, unsure if they can do it, especially if it’s their first time. The teachers have to get you on board quickly, and I noticed a pattern – after a gentle warmup, they’d always start with a really simple step.

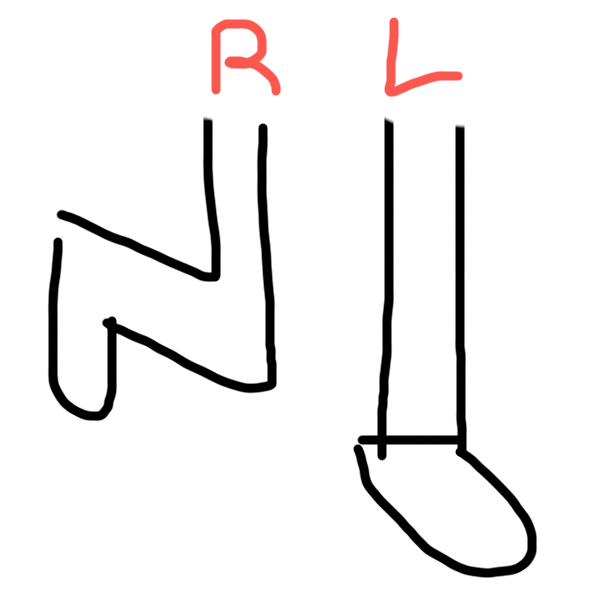

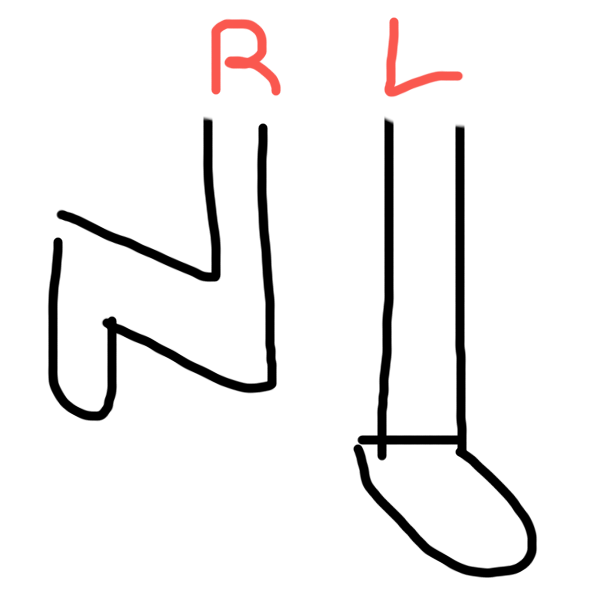

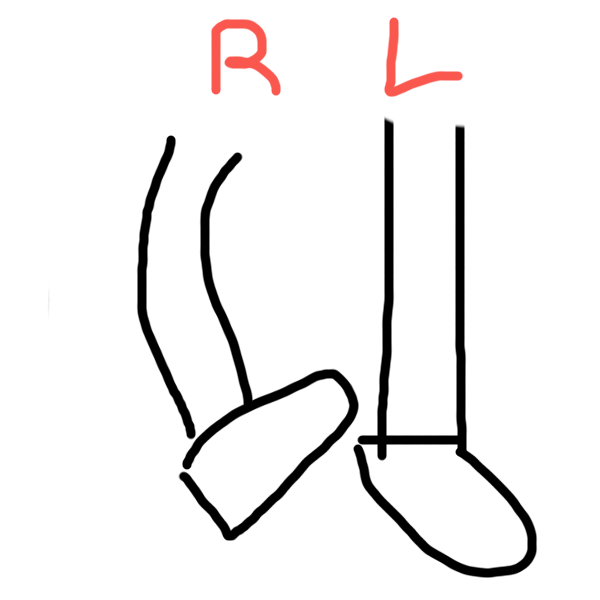

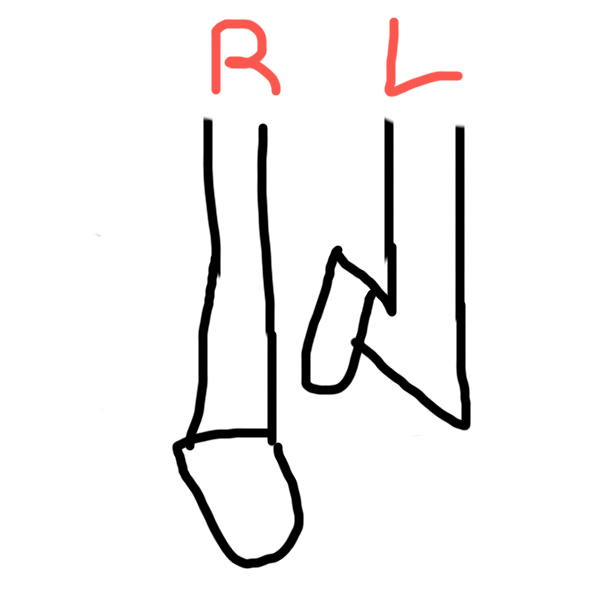

At this point I demonstrated with a simple step on stage. I don’t have any video of this, so you’ll have to make do with crude MS Paint drawings.

This is a kick, kick, step.

Stand on my left leg, and raise my right leg in the air. Bent at the knee, foot pointing back.

Swing the right leg forward into a kick.

Swing the right leg back up, completing the kick.

Swing the right leg forward again for a second kick.

Step down onto the right leg, and lift my left leg into the air.

Kick, kick, step.

This was a smart way to start the class. If you can balance on one foot, you can do this move. You get that sense of achievement, and there’s something satisfying about a whole room of people stepping in unison.

From there, the class would gradually build to more complicated things – moves, turns, routines. But we’d always build something new in small steps, not doing too much at once.

Starting small is a great way to learn a new skill, and this approach can apply in a lot of areas.

If you’re trying to learn a skill or embed a new habit, make the bar for success extremely low. This is a one-two punch:

- You’ll get that sense of achievement, the dopamine hit of reaching your goal.

- You avoid the negative emotion of setting the bar too high and falling short.

The latter is a common mistake when we learn new skills as adults. We’re used to being good at things; we have high standards for ourselves. Then we try to learn something new, and we set our goal far too high, then we fall short, we bounce off.

How many people have done this? Picked up a new skill, done it once, you weren’t instantly good at it, so you never did it again. [A lot of guilty faces in the audience for this one.]

We don’t like to be bad at things – but we can only learn if we push through the period of not being very good. When we’re a beginner and we don’t know very much, we need to set small goals and step forward gradually.

This is where we come back to AI, to prompt engineering – which have been new skills for many of us in the last year or two.

When I first tried these new generative AI tools, I was lured in by the big and flashy stuff. That’s what grabbed headlines; that’s what grabbed my attention. I was reading Twitter, I thought “that looks fun, I want do to that”.

I set a very high bar for what I wanted to achieve, and I wanted to replicate those cool results – but I didn’t know what I was doing, so I couldn’t do any of that cool stuff. So I bounced off for months. I ignored these tools, because of the bitter taste of those initial failures.

I only started doing useful stuff with these tools when I lowered my expectations. I wanted a small first step. What’s a small step for AI? It’s a simple prompt; a single question; a single sentence.

I went back and found the first ChatGPT sessions where I got something useful out of it. I was building a URL checker, I have a bunch of websites, I want to check they’re up. I wanted to write a script to help me. So I asked ChatGPT “how do I fetch a single URL”.

This is a simple task, something I could easily Google, and many of you probably already know how to do this. But that’s not the point – the point is that it gave me that initial feeling of success. It was the first time I had that sense of “ooh, this could be useful”.

I was able to build on that, and by asking more small questions I eventually got a non-trivial URL checker. A more experienced AI user could probably have written the entire program in a single prompt, and I couldn’t, but that’s okay – I still got something useful by asking a series of small, simple questions.

So start small! This is a really useful idea, and applies to so many things, not just dance or AI.

But I forget it so often, because it’s easy to be lured in by the hype, the impressive, the shiny. I have to keep reminding myself: start small, don’t overreach yourself.

But what happens when you want to move past the basics?

In dancing, the next step is finding a partner. A lot of swing dances are partnered dances, there’s a leader and a follower. The leader initiates the moves, the follower follows, together they make awesome dance magic.

If you go back to the same classes and events, you dance with the same people. You get to know them, what they can do, what they like and what they don’t. You develop a sense of rapport, and this is so important when dancing. You have to find the right level of trust, what you both feel comfortable doing. Maybe you’re happy to dance a move with one person, but not with another.

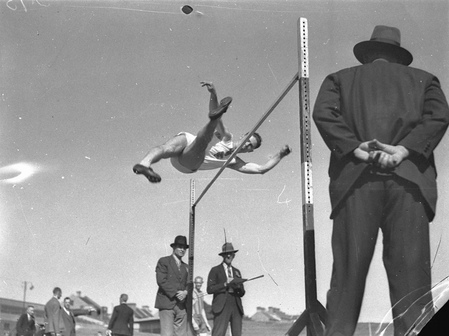

Let’s look at a few examples.

In the photo above, the couple are dancing some sort of hand-to-hand jitterbug routine. This is the sort of thing that you can teach a beginner in a couple of hours; nothing weird is going on here; it’s the sort of move most dancers would happily dance with a complete stranger.

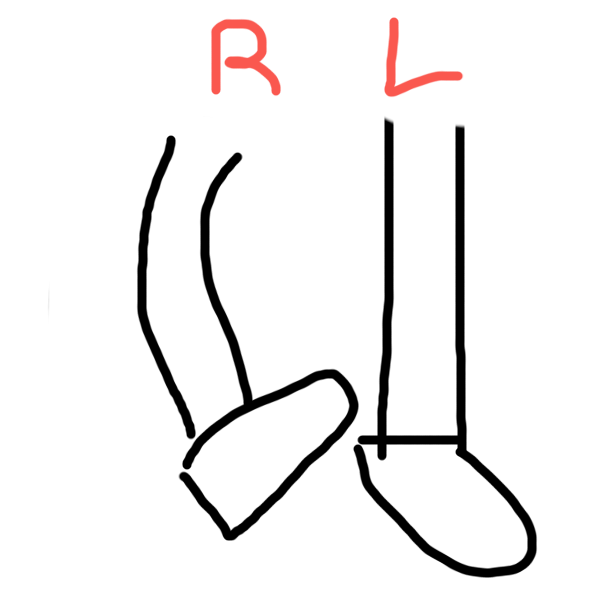

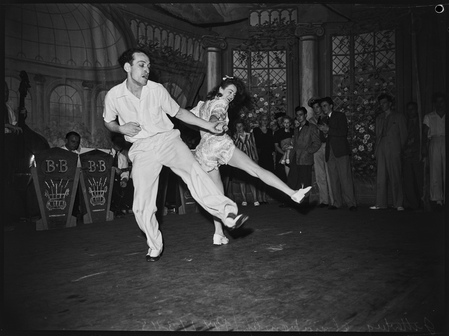

Next up, we have tandem Charleston.

In this dance, the follower stands in front of the leader, they both face forward, and they’re connected by their hands at their sides. It’s hard for them to talk to each other, and the follower can’t see their leader.

This is a fun dance that’s easy to teach to beginners, but you can see it’s a bit more of an awkward position. A lot of followers (especially women) aren’t super comfortable dancing this with strangers, and would walk away if you tried it on a social dance floor.

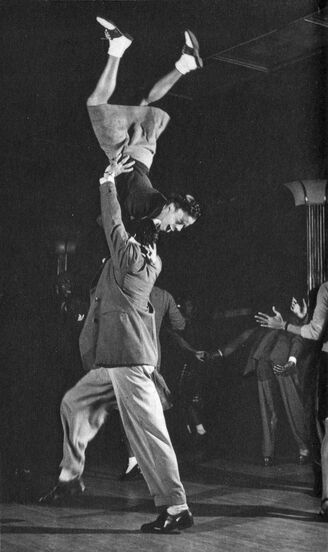

And finally we have aerials. This is when your feet leave the ground, you’re lifted up in the air. In this case, the leader has lifted their follow and flipped her entirely upside down – and hopefully a few seconds later, she returned to the ground safely!

This is obviously a much riskier move, and requires a lot of trust between the two partners. You would never do this with a stranger, and I know a lot of experienced dancers who don’t go near moves like this.

The point is that trust isn’t binary. You have to find the right level of trust with your partner.

What do you feel comfortable doing?

And that question applies to generative AI as much as it does to dancing. If you’re using it for fun stuff, to make images or videos, that’s one thing. If you’re using them for knowledge work, if you’re relying on their output, that’s quite another. If you want to use these tools, you have to know how much you trust them.

The right level of trust isn’t absolute faith or complete scepticism; it’s somewhere in the middle. Maybe you trust it for one thing, but not another.

I’ve seen a lot of discussions of prompt engineering that focus on the mechanical skills, without thinking about trust. “Type in this text to get these results.” That’s important, but it’s no good having those skills if you can’t trust and use the results you get.

How do we learn to trust AI? I think this will be a key question as we use more and more of these tools. How do we build mental models of what we can trust? How do we help everyone find the right level of trust for them? How do we work out when we do and don’t trust them? The same techniques we’ve already discussed can help – start small, and work your way up.

When you dance with a stranger, you don’t jump straight to the most complex move in your repetoire – you start with simpler moves, and you get a sense of each other’s comfort. Are you both dancing energetically? Confidentally? Does it feel safe to do something more complicated? Or is your partner nervous? Wary? Perhaps at the edge of their comfort zone?

We can do something similar with AI. One thing I’ve found useful when testing new tools is to ask it something simple, something I already know how to do. If I see it doing a good job, I can start to trust it for similar tasks. If it completely messes up, I know I can’t trust it for this.

So what do I trust AI for? I want to give you a few practical examples.

I think it’s important to work in areas where you already have a decent understanding. We know these tools can hallucinate. We know they can make stuff up. We know they can go off the rails.

The safeguard is us, the human, and we need to be able to spot when they’ve gone off the rails and need guiding back to the straight and narrow.

We all have different areas of competence and expertise – the areas where we trust AI are going to be different for each us. So I might trust an AI to tell me about digital preservation or dance styles, but I wouldn’t ask it questions about farming or firefighting or frogs.

Let’s look at a few examples.

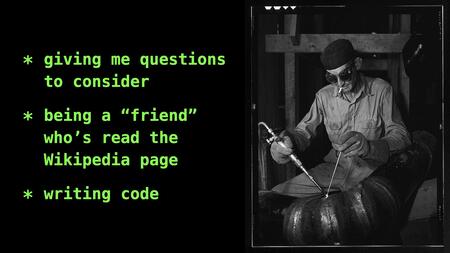

One thing I use AI tools for is to generate a whole bunch of ideas, a whole bunch of questions, a sort of brainstorming tool. I give it a discussion topic, and rather than asking it for answers, I ask it to tell me what sort of things I should be considering.

I used ChatGPT to help me write this talk. I described the broad premise of the talk, and I asked it to tell me what aspects I should consider. What should I discuss? What could I say? What might my audience want to hear? I didn’t use any of its output directly, but it gave me some stuff to think about. Some of it was bad, some of it I already had, some of its suggestions were useful additions to the talk.

This is an inversion of the prompter/promptee relationship: I’m not giving the computer a topic to think about it; it’s giving me topics to think about.

What if I want more than ideas, what if I want some facts?

AI tools are unreliable sources of facts, and you always have to be careful. They can make up nonsense, and repeat them as if they’re facts with complete confidence and authority. It’s mansplaining as a service.

But it’s not like they don’t know any facts, and sometimes they do get them right. The right level of trust isn’t absolute faith or complete scepticism, it’s somewhere in between. How do we know when to trust them?

I’ve settled on the idea that AI is like a friend who’s read a Wikipedia article – maybe after having a few beers. There’s definitely something behind what they’re remembering, but it may not always be right. I wouldn’t rely on it for anything important, but if often contains a clue to something which is true – a name, an idea, some terminology that leads me towards more trustworthy reference material.

And finally, I use AI for writing code.

But again, I stick to areas where I already have some expertise. I use these tools to write code in languages I use, frameworks I’m familiar with, problems that I can understand.

When I’m working with a team of human developers, I sometimes have to pass on doing a code review because I don’t know enough to do a proper review. That’s my threshold for using AI tools – if I wouldn’t be comfortable reviewing the code, I don’t trust the two of us to write it together. There’s too much of a risk that I’ll miss a subtle mistake or major bug.

But that still leaves a lot of use cases!

I use it for a lot of boilerplate code. It’s a good way to get certain repetitive utility functions. And it’s particularly useful when there are tools that have a complicated interface, and I have to get the list of fiddly options correct (ffmpeg springs to mind). It’s quite tricky to get the right set of incantations, but once I’ve got them it’s easy to see if they’re behaving correctly.

So those are a few of the things I trust generative AI for. These are more evolutionary than revolutionary – these AI tools have become another thing in my toolbox, but they haven’t fundamentally changed the way I work. (Yet.)

Of course, you’ll trust them for different things. Don’t take this as a prescriptive list; take it as some ideas for how you might use AI.

So like a slow jazz number at the end of the evening, let’s wrap things up.

Being a great dancer: yes, it requires the technical skills. You need to know the footwork, the moves, the rhythm. But it’s also about trust, knowing your partner, working out what they’re comfortable with.

The same thing is true of using AI. You need to know how to write prompts, how to get information, how to get the results you want. But you also need to know if you trust those results, when you can rely on the output.

We need both of those skills to be great users of AI.