Agile and iterative project management

Earlier today, I gave a talk for the the Open Life Science Program about agile and iterative project management. I was talking about how READMEs serve as the first point of contact for a project; how they get new users interested in and excited about the project.

The cohort calls are recorded, and I’ll add a link to the video when it’s posted. In the meantime, you can download my slides as a PDF, and I’ll add some notes shortly.

Slides and notes

Title slide.

I’m going to talk about what agile and iterative project management methods are, where they come from, and why they might be good for your project.

I work at Wellcome Collection, a museum and library in London, and we do iterative project management, so I’ll be drawing on examples of my own work for this talk.

Agile is an approach to project management tool; it’s a way of managing your tasks. You might be doing some of it already, so I want to jump straight in.

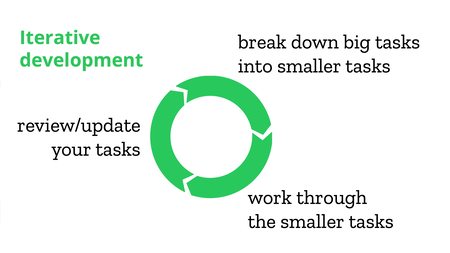

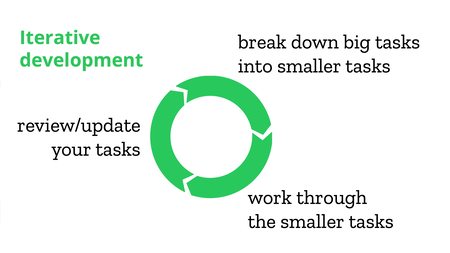

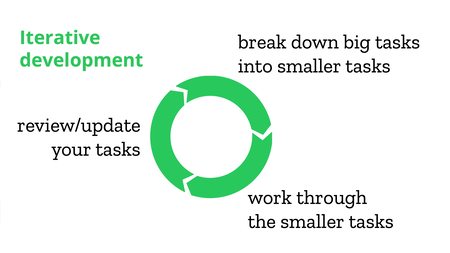

In an iterative project, you:

- Break down your tasks into smaller tasks

- Work through the smaller tasks

- Review/update your tasks

Most people are already familiar with steps 1 and 2; but step 3 is super important and it’s the bit people often miss. This cycle gets us a fast feedback loop for our task management.

Working in this iterative style gives you a number of benefits:

- you can react to new info or requirements

- gather feedback quickly

- always be doing something important

You’re not tied to a plan you made six months ago that’s no longer relevant; because you’re doing a regular review of your plans you can stay up-to-date.

The best example from recent years is the COVID-19 pandemic. A lot of plans got thrown up in the air in early 2020; if you already used to an iterative approach to project management, you were better placed to adapt to changing circumstances.

Repeat previous slide.

This is iterative development.

This is an idea that’s come out of the software development community, and seen a massive spike in the last decade or so. Why’s there such a buzz? To understand this, we need to understand what came before.

Waterfall icon by Luis Prado on the Noun Project. Used with a NounPro subscription.

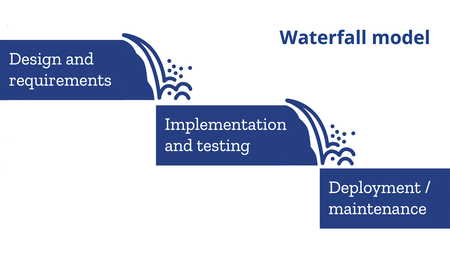

The old approach to software development was called “waterfall”, and this diagram gives an idea why. The project gets broken down into distinct phases, and each phase blocks the next phase.

You started with all your design, requirements finding, business analysis. That happened upfront, and produced a spec, a written document that was usually several inches thick. You didn’t do any coding until the spec was written.

Then you’d give the spec to a team of programmers, who’d write all the code, and hand off a single version of the software for distribution and deployment.

This comes from a time when computing was very different – computers were much less powerful, they weren’t as numerous, and most software was distributed on plastic disks rather than over the web. There were very slow feedback loops. Once software was shipped, it’s done.

In the 21st century, software development has changed, and this model was less and less appropriate.

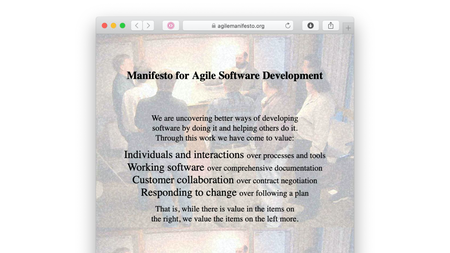

In 2001, a group of developers published the “agile manifesto”, which helped popularise these ideas.

This started the big push towards agile that we see today – some of it was new ideas, some of it was a fresh coat of paint on existing ideas. (Contrary to popular belief, programmers didn’t invent come up with every good idea that exists.)

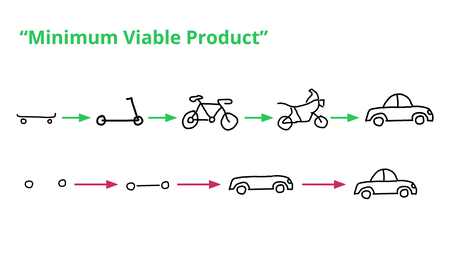

One of the big ideas to come out of the agile manifesto was the idea of a “minimum viable product” or “MVP”. We’ve talked about how you break a big task down into smaller tasks; MVP says that we should try to iterate on working versions. Each of those smaller steps should produce useful output that we can use, react to, get feedback on.

This has obvious advantages for commercial software, but it’s great for research as well – we can get feedback and review our assumptions as we go along.

This is an almost clichéd diagram when talking about MVP: the evolution of wheeled transport. Following MVP means you go from a skateboard, to a scooter, to a pushbike, to a motorbike, to a car. We could stop at any point and still have something useful.

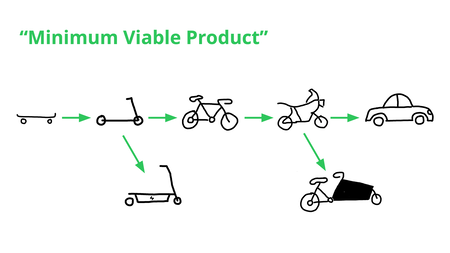

But I think this diagram actually undersells MVP – if we take an MVP mindset, we can react to new information and feedback. We don’t have to go all the way to the car.

Maybe we discover that people love the form factor of the scooter but want to go up hills – so rather than making a pushbike, we should make an e-scooter. Or maybe the motorbike is a flop, and what people really wanted was a bike with more carrying capacity, so we should switch to cargo bikes.

This is another phrase you might have heard, which is a pithy form of the agile manifesto. Failure is a necessary part of iteration: you make mistakes, and you learn from them.

I include this both because it’s a cliché, and also to illustrate that waterfall and agile aren’t better/worse than each other; they’re appropriate in different scenarios. They exist on a spectrum.

Making lots of mistakes on the way to success is fine if you’re making a game, or a website, or an app. It’s not so good if you’re designing a plane, a banking service, or a drug trial.

Iterative approaches have become very popular, but waterfall still has a place.

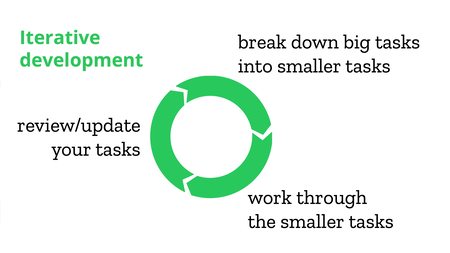

Repeat earlier slide.

So again, iterative development. Break down tasks, work through them, review/update on a regular scheudle.

This is the core idea, and you can interpret it in many different ways. There are lots of implementations of agile, all slightly different, with lots of process and tea ceremony that we don’t have time to go into today. You can read more about those on your own time.

But I do want to give you one example, to make this a bit more concrete.

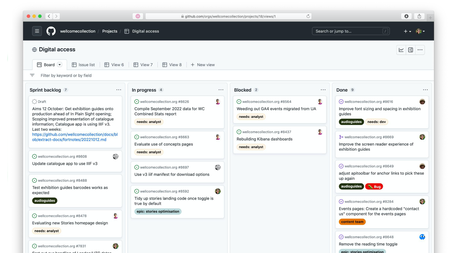

This is a real-world example, of how one of my teams does agile project management. We use GitHub to manage tasks, using Issues, and this is our project board. We have four columns: sprint backlog, in progress, blocked, and done.

The word sprint is an Agile term, and for us it’s a two-week span of work. Remember I talked about the importance of reviewing your plans? A sprint is our tool for doing that.

At the start of each sprint, we have a planning meeting where we review the tasks in the backlog, and decide what’s most important. What do we want to work on for the next two weeks? Then we work on tasks, which gradually move from left-to-right across the board. (This is a form of kanban.)

Two weeks later, at the end of the sprint, we have a new planning meeting. We review what we’ve done, what’s next, and we organise the backlog. We might add tasks, remove them, or put them in a different order.

We do one sprint after another, and the cycle means we remember to go back and review tasks, so we’re always working on something important.

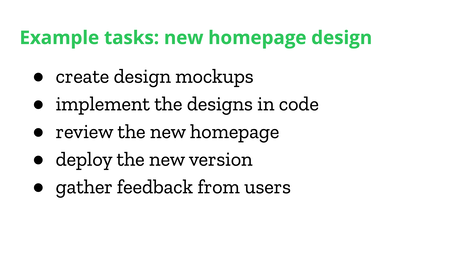

I also wanted to give an example of how we might break down a big task (“new homepage design”) into smaller tasks.

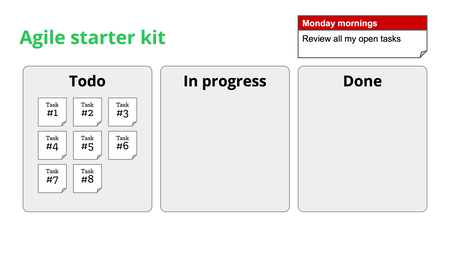

This is a slightly more abstract version of that example, a sort of “agile starter kit”.

Recap slide.

Wrap up slide.